By David Abel | The Boston Globe | 9/14/1999

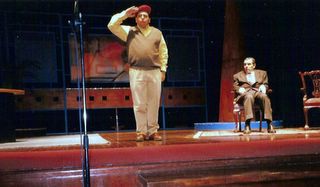

By David Abel | The Boston Globe | 9/14/1999CARACAS - Swaggering on the stage in a floppy red beret, the stocky speaker halts his long, epithet-loaded diatribe, winks and points proudly at pals in the crowd, then launches anew into his attack on the "corrupt nest of vipers" who dare criticize him.

This is not a speech by Hugo Chavez, the feared and revered leader of a failed 1992 military coup who was elected president in December by a sweeping majority. It's an actor mimicking the president in a satire that has been packing in audiences since Chavez took office.

But Rolando Salazar, who caricatures the president with studied detail, is not sure if his play is a comedy or tragedy.

"Chavez says he respects freedom of expression, but you don't know," said Salazar after a recent performance of "The Reconstitution," named for the president's controversial plan to rewrite the nation's 38-year-old constitution. "We could be shut down tomorrow. We don't know. Anything can happen at any moment."

Freedom of expression remains alive and aggressive in this South American nation of 23 million people. The evidence is in the pages of critical editorials in the capital's numerous newspapers, on radio talk shows across the country, and on the sophisticated nightly news programs on TV.

But critics of Chavez's increasingly centralized government fear their dissenting voices may soon be silenced, much as the nation's Supreme Court and Congress were usurped and all but shut down by a new constitutional assembly, loyal to Chavez, that has proclaimed itself the nation's "supreme" body.

Americans will get a chance to take their own measure of Chavez next week when he speaks to the United Nations General Assembly and then visits top officials in Washington, which banned him from entering the country for several years after the bloody 1992 coup attempt. Venezuela gets more than average attention from Washington because it supplies a significant portion of US oil imports.

"Free expression will fall off," predicted the historian Jorge Olavarria, one of only 10 Chavez opponents elected in July to sit on the 131-person constitutional assembly. "Right now it's great camouflage for the regime. But it's rubbish to say there's liberty here. This is just the beginning."

Olavarria and others say they already see the warning signs of an impending clampdown: government paranoia about its image, verbal attacks on specific journalists, and an evident distaste for democracy's checks and balances.

The constitutional assembly has already acted against the mounting criticism. After announcing that the assembly would take action to reverse the increasingly ominous picture of events being painted by the international press, pro-Chavez assemblyman Edmundo Chirinos said in late August, "The proliferation of articles against the process Venezuela is undergoing is not casual; it is an orchestrated campaign."

Chavez vows that his government has no intention of ending free expression. And those who say the opposite, he argues, seek to discredit his "peaceful, social revolution" with falsehoods.

"We aren't going to raise the flag of tyranny or arbitrariness or persecution," Chavez said during a call-in radio program last month. Since February, when he took office, Venezuelans have had "absolute freedom of press, freedom of thought, freedom of expression," Chavez insisted.

His supporters point out that Chavez's predecessors often flouted free speech. It was not uncommon for government officials to tape journalists' conversations, threaten editors, pressure advertisers, and pay bribes for favorable coverage.

Under former President Rafael Caldera, the government imposed strict exchange-rate controls, forcing the Venezuelan press to approach the government for the dollars needed pay for imported newsprint. Newspapers favorable to the government often had a full supply of paper; those known to be critical had to cut back on the number of pages they published because officials delayed approval of the dollar exchanges they needed to import paper.

Press freedoms in Venezuela have never been as broad as in the United States. Journalists are required to have a degree from a Venezuelan university and membership in the national journalists' union. Defamation is a criminal offense in Venezuela, punishable by up to 18 months in prison.

Today, the critics fear what they call a trend toward strongman rule by Chavez, 45, a former Army lieutenant colonel and paratrooper whose bloody uprising in 1992 left dozens dead. Just before he was elected, the Caracas press published unsubstantiated reports that Chavez planned to have critical journalists and opposition leaders shot if he lost the election.

Today, the critics fear what they call a trend toward strongman rule by Chavez, 45, a former Army lieutenant colonel and paratrooper whose bloody uprising in 1992 left dozens dead. Just before he was elected, the Caracas press published unsubstantiated reports that Chavez planned to have critical journalists and opposition leaders shot if he lost the election."History indicates as people accumulate power they are less tolerant of dissenting voices," said Marylene Smeets, Americas program coordinator for the Committee to Protect Journalists, a New York-based organization that works to protect press freedoms. "The possibility exists there could be clamping down on the press. That's why the situation calls for monitoring."

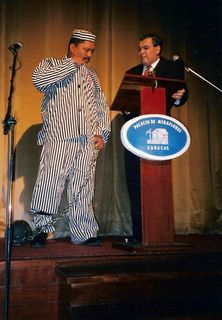

In the closing monologue of the hit satire, which has been attended by members of Chavez's cabinet, congress members, and state governors, the show's host recalls General Carlos Soublette, a 19th-century president.

When that president learned of a satirical play in which he was lampooned, Soublette said all was well in Venezuela so long as "the people are able to mock their president."

The country would be in trouble, he goes on, "when the president makes a mockery of the people."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com.

Copyright, The Boston Globe