Economic Woes Darken Outlook

Economic Woes Darken OutlookBy David Abel | Globe Staff | 3/31/2002

BUENOS AIRES - Three months ago, the shattered glass of bank windows littered the city's streets, graffiti screamed from seemingly every corner for the overthrow of the nation's politicians, and daily looting, rioting, and marches led to bloodshed, with one outpouring of fury leaving 27 dead in front of the president's pink palace.

Today, late summer rains have washed away much of the graffiti, banks have replaced their broken windows with metal shutters, and the bloody marches have dwindled to random roadblocks and groups of protesters clanging pots and pans.

Three months after Argentina defaulted on the largest debt of any nation in history, and after this once-prosperous land of European immigrants saw a provincial governor become the fifth president in two weeks, the rage here has given way to a mix of fear and resignation.

"I come from a sad country," says Carlos Toscano, a cab driver who quoted Jorge Luis Borges, Argentina's literary giant, echoing many others like him who have seen their wages cut in half and their workday double in length to make ends meet.

The country's current calm, Toscano and others insisted, is deceptive. Without an elected government and with pressure building for political change, the outlook for Argentina is getting worse.

Inflation is creeping up, and the value of the peso, once equal to the dollar, has plummeted by a third. Life savings for many residents have either vanished with the January devaluation or are out of reach, the result of strict controls to prevent a run on banks.

Unemployment, crime, and poverty rates are rising, and many in the upper and middle classes are fleeing the country while a growing number of working class families are losing their homes. Neither the International Monetary Fund nor Washington appears likely to bail out the country through loans or grants.

"I inherited a bankrupt country on the verge of anarchy," Eduardo Duhalde, who took over as president on Jan. 1, said in a nationally televised speech before the country's congress this month. "There is a crisis of representation. People do not have confidence in their representatives and their courts."

A century ago, Argentina was ranked the seventh wealthiest nation in the world, with a per-capita income greater than France, Japan, Spain, and nearly that of the United States. Then came decades of corrupt civilian governments, populist demagogues, and a succession of harsh military dictatorships that culminated in the early 1980s with the murder of some 30,000 people.

Now, across this large country rich in natural resources, with its elegant capital styled after Paris and an educated middle class rivaling most of the developed nations, Argentines are asking themselves a question that previous generations have asked: What is wrong with this country?

Sitting on a beach about 200 miles south of here in the resort town of Pinamar, where "for sale" signs hang on many homes, Mariana Rojas explains it this way: "Unlike normal countries, the politicians here don't care about the people," says Rojas, 27, who's moving back home to live with her family after losing her job as an advertising account manager. "They're in it for themselves. The rest of us just end up suffering."

About 1,500 miles to the south, at the tip of Tierra del Fuego, Marcelo Salina sits glumly by a computer at a cafe in the mountain-rung city of Ushuaia, mulling a move to another country. Several weeks ago, the 27-year-old was a computer programmer for Sanyo and AIWA. When both firms closed, he took a job for a fraction of the pay at a local Internet cafe.

"You could say that I'm lucky I found a job," he says. "This is not what I want to do, but it's better than nothing."

In a nation where money is increasingly scarce, Salina is fortunate to have any income. About a quarter of Argentines are unemployed and nearly half live below the poverty line. One newspaper here reported that nearly 50 percent of all high school students this year are dropping out to help their families earn a living.

In a nation where money is increasingly scarce, Salina is fortunate to have any income. About a quarter of Argentines are unemployed and nearly half live below the poverty line. One newspaper here reported that nearly 50 percent of all high school students this year are dropping out to help their families earn a living.The crisis has even extended to the one refuge Argentines have long taken to reclaim their glory: soccer. A wave of violence spread through stadiums around the capital this summer, resulting in four deaths and dozens of injuries. The bloodshed has led to calls to suspend the season.

Meanwhile, as the government struggles to pay federal employees and keep hospitals open - despite more than $140 billion dollars in debt - the public has shown little patience. At a national meeting of neighborhood associations two weeks ago, representatives drafted a resolution calling for, among other measures, the nationalization of banks, nonpayment of the debt, and a grass-roots campaign to "kick out all the politicians."

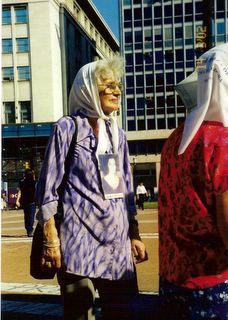

With the economy in tatters, nearly everyone has been affected. Mirta Acuna de Baravalle, 77, who lost her pregnant daughter 25 years ago during the nation's "dirty war" and since then has spent nearly every Thursday protesting in front of the president's office, has yet to collect on the government's pledge to pay reparations to the relatives of those who disappeared. "It's just another robbery," Baravalle said. "Unfortunately, we've come to expect that here."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com.

Copyright, The Boston Globe