Nowhere is the Damage to the Earth's Ozone Layer More Dangerous -- Residents Have Sunburns and Cancer to Prove it.

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 4/02/2002

USHUAIA, Argentina - Frigid gusts make the trees grow sideways, penguins and sea lions slide from frosty beaches into icy waters, and flurries fall gently on the snow-capped glaciers ringing this small city at the bottom of the world.

It may feel like winter year-round, even recently in late summer, but the blustery assault of Antarctic winds at the southern tip of South America can be a cruel illusion.

Despite freezing temperatures and an occasional blizzard, the sun on a clear spring day in Ushuaia can burn more quickly and dangerously than the rays on a beach in Miami. In fact, on a cloudless day from late August to December, especially after a recent snowfall, there may be no more dangerous place on the planet to spend time outdoors.

"The sun is strong - but it's not warm," said Nicolas Gamarra, 42, who, after spending half his life in Ushuaia driving a taxi, ignored his company's advice last year to install a special film on the windshield of his cab. "Without heat, we don't worry."

Many people in the city, including Gamarra, wonder whether they should be more concerned. Every spring over the past two decades, an expanding hole more than two times the size of Europe opens in the ozone layer and exposes this pristine city's nearly 50,000 mainly fair-skinned residents to the most unfiltered ultraviolet light anywhere but the unpopulated tundra of Antarctica.

The result of damaging man-made chemicals released over decades into the atmosphere,  the ozone depletion over the Tierra del Fuego islands has worsened ever since scientists discovered the hole in the late 1970s. While the rate of thinning has begun to slow, ozone levels in the region have declined - sometimes to less than half normal levels - despite an international treaty signed in 1987 that banned ozone-destroying chemicals.

the ozone depletion over the Tierra del Fuego islands has worsened ever since scientists discovered the hole in the late 1970s. While the rate of thinning has begun to slow, ozone levels in the region have declined - sometimes to less than half normal levels - despite an international treaty signed in 1987 that banned ozone-destroying chemicals.

The ozone won't return to normal levels until at least the middle of this century and scientists see Tierra del Fuego as ground zero in the debate over the biological consequences of the hole. Already, scientists have observed that increased radiation in the region has damaged everything from the DNA of certain plants near Ushuaia to the growth of icefish eggs near Antarctica.

And now, for the first time, studies show a direct link between days when the ozone hole extended over the region and skin ailments sustained by people in Tierra del Fuego and in Punta Arenas, a city of about 150,000 just north of Ushuaia in Chile.

In February, Jaime Abarca, a dermatologist in Punta Arenas, and two Chilean climatologists published a study in the Framingham-based Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology that documented the first cases of blistering sunburns on days with significant depletions of ozone. Another Chilean dermatologist also recently published a study showing over seven years a 28 percent increase in cheilitis, the cracking of skin around the lips.

In the latest study, which won't be published for another six months, Abarca and a colleague document a 66 percent increase of skin cancer in Punta Arenas from 1987 to 2000. An earlier study by Argentine dermatologists found that cases of skin cancer in Ushuaia rose more than 50 percent between 1985 and 1995.

"This may be a very serious problem," Abarca said from his office in Punta Arenas. "Most of the people here don't even understand that they have to take care. Their skin is not adapted to sudden surges of ultraviolet light - and the ozone is not likely to improve for at least another 50 years."

Although pharmacies in the region market sunscreen in their display windows, setting them on pedestals like some shops feature perfume, few in this century-old former penal colony are worried about the ozone hole.

Scientists show graphs that make living in San Diego seem more dangerous. Dermatologists discount the skin cancer increases, attributing the rise to a growing and aging population. And the tourist office in the center of town doesn't offer information about the ozone hole because officials don't believe it's a serious problem - and they don't want to alarm the public.

For many others in Ushuaia,  the ozone hole is something they've heard of but know little about. In their last year in high school, Piatoni Flavio and Vanessa Delgado, both 17, shake their heads when asked what they've been taught about the ozone hole.

"Nothing," Flavio said.

the ozone hole is something they've heard of but know little about. In their last year in high school, Piatoni Flavio and Vanessa Delgado, both 17, shake their heads when asked what they've been taught about the ozone hole.

"Nothing," Flavio said.

Turning her back on the bright midday sun, Delgado said: "There's no information here."

Julio Rodriguez, a policeman who spends countless hours outside patrolling the streets, isn't worried, either. With Argentina's economy in tatters, its president unelected and the fifth to take office in the past three months, and unemployment, inflation, and crime rising throughout the country, there are other things to fret about.

"This country has so many problems right now, the least of my concerns is the environment," he said.

Those who have spent years studying the thinning ozone, like Susana B. Diaz, a scientist leading a team measuring radiation in Ushuaia, explain their lack of concern by drawing a picture of the Earth. In it, the city benefits from being at the bottom of the planet. Despite less ozone, Diaz and others say, sun rays pass through the atmosphere at a slanted angle, traveling through more ozone than those that enter more directly near the equator.

The soft-spoken scientist said she rarely, if ever, wears sunscreen and believes Abarca and officials in Punta Arenas, which broadcasts ozone alerts in local media using a red, yellow, and green-light warning system, are going overboard.

"What they are doing is making an alarm - overreacting," she said while pointing to graphs showing radiation levels lower than in San Diego. "They're giving people the idea that they can't go outside during the ozone hole. That's wrong."

One dermatologist, however, believes prudence is wiser than skepticism and counsels her patients to let their children play outside - but if it's spring, only with sunscreen.

Maria Monica Pages de Carlot is one of only four dermatologists in Ushuaia. She has made presentations at schools and pressed local authorities to air radio and TV advisories about the potential harm from the sun. After more than a decade working in Tierra del Fuego, seeing about 400 patients a month, she has treated a range of skin ailments. But it wasn't until two years ago that she really sensed the potential danger of living beneath the ozone hole.

On Oct. 12, 2000, hundreds of people lined the streets of Ushuaia for hours to attend the annual parade celebrating the city's founding. It so happened, and without any warning to the public, the ozone that day dropped to one of the most dangerous levels since scientists began monitoring the hole. After the parade, Carlot and the other dermatologists received an uncommonly large number of patients seeking treatment for severe sunburns.

"This was a surprise for us, but thankfully it hasn't been common," Carlot said. "We're really not sure what the long-term effects will be if the ozone hole doesn't improve. We need further studies."

For Abarca, all the information he and other scientists have compiled proves the hole's danger. With predictions still sketchy about when the ozone hole will ultimately close, he believes officials in Ushuaia are wrong to act otherwise.

He acknowledged that sun rays pass through more atmosphere in Ushuaia than in cities such as Buenos Aires or Boston, where ozone levels are far more normal. But he said the depleted ozone allows more of the short wavelengths of ultraviolet light - the most carcinogenic sun rays in the spectrum - to reach the ground than in any other populated area in the world.

"Is this not reason enough to be worried?" he asked.

And when the Argentines say residents are protected because  they almost always cover themselves head-to-toe to shield the cold, Abarca said he believes that's another reason the ozone hole is so dangerous. In spring, when temperatures warm and ozone declines, the fair-skinned people frequently shed their heavy parkas. With little exposure to the sun, they're more likely to sustain sunburns, especially if the sunlight is magnified by snow.

they almost always cover themselves head-to-toe to shield the cold, Abarca said he believes that's another reason the ozone hole is so dangerous. In spring, when temperatures warm and ozone declines, the fair-skinned people frequently shed their heavy parkas. With little exposure to the sun, they're more likely to sustain sunburns, especially if the sunlight is magnified by snow.

What's needed now, he and others argue, is increased education about the ozone depletion and a system that alerts residents throughout the bottom of South America when to expect a serious drop in ozone.

"No one wants to make the tourists go away," Abarca said. "But we are telling the truth, not overreacting. This is a problem that cannot be ignored."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com.

Copyright, The Boston Globe

Economic Woes Darken Outlook

Economic Woes Darken Outlook

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 3/31/2002

BUENOS AIRES - Three months ago, the shattered glass of bank windows littered the city's streets, graffiti screamed from seemingly every corner for the overthrow of the nation's politicians, and daily looting, rioting, and marches led to bloodshed, with one outpouring of fury leaving 27 dead in front of the president's pink palace.

Today, late summer rains have washed away much of the graffiti, banks have replaced their broken windows with metal shutters, and the bloody marches have dwindled to random roadblocks and groups of protesters clanging pots and pans.

Three months after Argentina defaulted on the largest debt of any nation in history, and after this once-prosperous land of European immigrants saw a provincial governor become the fifth president in two weeks, the rage here has given way to a mix of fear and resignation.

"I come from a sad country," says Carlos Toscano, a cab driver who quoted Jorge Luis Borges, Argentina's literary giant, echoing many others like him who have seen their wages cut in half and their workday double in length to make ends meet.

The country's current calm, Toscano and others insisted, is deceptive. Without an elected government and with pressure building for political change, the outlook for Argentina is getting worse.

Inflation is creeping up, and the value of the peso, once equal to the dollar, has plummeted by a third. Life savings for many residents have either vanished with the January devaluation or are out of reach, the result of strict controls to prevent a run on banks.

Unemployment, crime, and poverty rates are rising, and many in the upper and middle classes are fleeing the country while a growing number of working class families are losing their homes. Neither the International Monetary Fund nor Washington appears likely to bail out the country through loans or grants.

"I inherited a bankrupt country on the verge of anarchy," Eduardo Duhalde, who took over as president on Jan. 1, said in a nationally televised speech before the country's congress this month. "There is a crisis of representation. People do not have confidence in their representatives and their courts."

A century ago, Argentina was ranked the seventh wealthiest nation in the world, with a per-capita income greater than France, Japan, Spain, and nearly that of the United States. Then came decades of corrupt civilian governments, populist demagogues, and a succession of harsh military dictatorships that culminated in the early 1980s with the murder of some 30,000 people.

Now, across this large country rich in natural resources, with its elegant capital styled after Paris and an educated middle class rivaling most of the developed nations, Argentines are asking themselves a question that previous generations have asked: What is wrong with this country?

Sitting on a beach about 200 miles south of here in the resort town of Pinamar, where "for sale" signs hang on many homes, Mariana Rojas explains it this way: "Unlike normal countries, the politicians here don't care about the people," says Rojas, 27, who's moving back home to live with her family after losing her job as an advertising account manager. "They're in it for themselves. The rest of us just end up suffering."

About 1,500 miles to the south, at the tip of Tierra del Fuego, Marcelo Salina sits glumly by a computer at a cafe in the mountain-rung city of Ushuaia, mulling a move to another country. Several weeks ago, the 27-year-old was a computer programmer for Sanyo and AIWA. When both firms closed, he took a job for a fraction of the pay at a local Internet cafe.

"You could say that I'm lucky I found a job," he says. "This is not what I want to do, but it's better than nothing."

In a nation where money is increasingly scarce, Salina is fortunate to have any income. About a quarter of Argentines are unemployed and nearly half live below the poverty line. One newspaper here reported that nearly 50 percent of all high school students this year are dropping out to help their families earn a living.

In a nation where money is increasingly scarce, Salina is fortunate to have any income. About a quarter of Argentines are unemployed and nearly half live below the poverty line. One newspaper here reported that nearly 50 percent of all high school students this year are dropping out to help their families earn a living.

The crisis has even extended to the one refuge Argentines have long taken to reclaim their glory: soccer. A wave of violence spread through stadiums around the capital this summer, resulting in four deaths and dozens of injuries. The bloodshed has led to calls to suspend the season.

Meanwhile, as the government struggles to pay federal employees and keep hospitals open - despite more than $140 billion dollars in debt - the public has shown little patience. At a national meeting of neighborhood associations two weeks ago, representatives drafted a resolution calling for, among other measures, the nationalization of banks, nonpayment of the debt, and a grass-roots campaign to "kick out all the politicians."

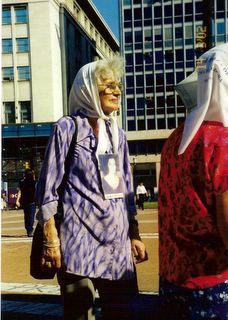

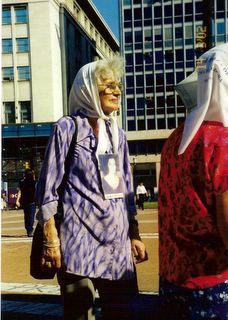

With the economy in tatters, nearly everyone has been affected. Mirta Acuna de Baravalle, 77, who lost her pregnant daughter 25 years ago during the nation's "dirty war" and since then has spent nearly every Thursday protesting in front of the president's office, has yet to collect on the government's pledge to pay reparations to the relatives of those who disappeared. "It's just another robbery," Baravalle said. "Unfortunately, we've come to expect that here."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com.

Copyright, The Boston Globe

By David Abel | The Boston Globe | 9/14/1999

By David Abel | The Boston Globe | 9/14/1999

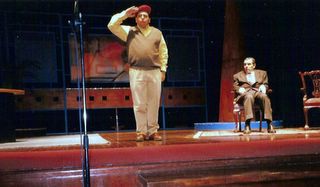

CARACAS - Swaggering on the stage in a floppy red beret, the stocky speaker halts his long, epithet-loaded diatribe, winks and points proudly at pals in the crowd, then launches anew into his attack on the "corrupt nest of vipers" who dare criticize him.

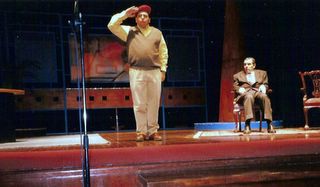

This is not a speech by Hugo Chavez, the feared and revered leader of a failed 1992 military coup who was elected president in December by a sweeping majority. It's an actor mimicking the president in a satire that has been packing in audiences since Chavez took office.

But Rolando Salazar, who caricatures the president with studied detail, is not sure if his play is a comedy or tragedy.

"Chavez says he respects freedom of expression, but you don't know," said Salazar after a recent performance of "The Reconstitution," named for the president's controversial plan to rewrite the nation's 38-year-old constitution. "We could be shut down tomorrow. We don't know. Anything can happen at any moment."

Freedom of expression remains alive and aggressive in this South American nation of 23 million people. The evidence is in the pages of critical editorials in the capital's numerous newspapers, on radio talk shows across the country, and on the sophisticated nightly news programs on TV.

But critics of Chavez's increasingly centralized government fear their dissenting voices may soon be silenced, much as the nation's Supreme Court and Congress were usurped and all but shut down by a new constitutional assembly, loyal to Chavez, that has proclaimed itself the nation's "supreme" body.

Americans will get a chance to take their own measure of Chavez next week when he speaks to the United Nations General Assembly and then visits top officials in Washington, which banned him from entering the country for several years after the bloody 1992 coup attempt. Venezuela gets more than average attention from Washington because it supplies a significant portion of US oil imports.

"Free expression will fall off," predicted the historian Jorge Olavarria, one of only 10 Chavez opponents elected in July to sit on the 131-person constitutional assembly. "Right now it's great camouflage for the regime. But it's rubbish to say there's liberty here. This is just the beginning."

Olavarria and others say they already see the warning signs of an impending clampdown: government paranoia about its image, verbal attacks on specific journalists, and an evident distaste for democracy's checks and balances.

The constitutional assembly has already acted against the mounting criticism. After announcing that the assembly would take action to reverse the increasingly ominous picture of events being painted by the international press, pro-Chavez assemblyman Edmundo Chirinos said in late August, "The proliferation of articles against the process Venezuela is undergoing is not casual; it is an orchestrated campaign."

Chavez vows that his government has no intention of ending free expression. And those who say the opposite, he argues, seek to discredit his "peaceful, social revolution" with falsehoods.

"We aren't going to raise the flag of tyranny or arbitrariness or persecution," Chavez said during a call-in radio program last month. Since February, when he took office, Venezuelans have had "absolute freedom of press, freedom of thought, freedom of expression," Chavez insisted.

His supporters point out that Chavez's predecessors often flouted free speech. It was not uncommon for government officials to tape journalists' conversations, threaten editors, pressure advertisers, and pay bribes for favorable coverage.

Under former President Rafael Caldera, the government imposed strict exchange-rate controls, forcing the Venezuelan press to approach the government for the dollars needed pay for imported newsprint. Newspapers favorable to the government often had a full supply of paper; those known to be critical had to cut back on the number of pages they published because officials delayed approval of the dollar exchanges they needed to import paper.

Press freedoms in Venezuela have never been as broad as in the United States. Journalists are required to have a degree from a Venezuelan university and membership in the national journalists' union. Defamation is a criminal offense in Venezuela, punishable by up to 18 months in prison.

Today, the critics fear what they call a trend toward strongman rule by Chavez, 45, a former Army lieutenant colonel and paratrooper whose bloody uprising in 1992 left dozens dead. Just before he was elected, the Caracas press published unsubstantiated reports that Chavez planned to have critical journalists and opposition leaders shot if he lost the election.

Today, the critics fear what they call a trend toward strongman rule by Chavez, 45, a former Army lieutenant colonel and paratrooper whose bloody uprising in 1992 left dozens dead. Just before he was elected, the Caracas press published unsubstantiated reports that Chavez planned to have critical journalists and opposition leaders shot if he lost the election.

"History indicates as people accumulate power they are less tolerant of dissenting voices," said Marylene Smeets, Americas program coordinator for the Committee to Protect Journalists, a New York-based organization that works to protect press freedoms. "The possibility exists there could be clamping down on the press. That's why the situation calls for monitoring."

In the closing monologue of the hit satire, which has been attended by members of Chavez's cabinet, congress members, and state governors, the show's host recalls General Carlos Soublette, a 19th-century president.

When that president learned of a satirical play in which he was lampooned, Soublette said all was well in Venezuela so long as "the people are able to mock their president."

The country would be in trouble, he goes on, "when the president makes a mockery of the people."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com.

Copyright, The Boston Globe

Puerto Ricans Vote on Political Status

Puerto Ricans Vote on Political Status

David Abel | The Christian Science Monitor | 12/11/1998

SAN JUAN, PUERTO RICO -- Americans are not famous for their knowledge of other lands.

So it may come as a surprise to many that a small island in the Caribbean, more than 1,000 miles southeast of Miami, will vote Sunday on whether to become the 51st US state.

More than 2 million people in Puerto Rico, a strategically important gateway to the Caribbean seized by the United States 100 years ago during the Spanish-American War, will seek for the third time an end to their lingering national limbo.

For decades this quasi-colony has existed as a US "commonwealth" - a sort of halfway house of Americanness devised in 1952. But this year, for the first time, it appears the faction intent on adding another star to the US flag will win most of the votes.

While the plebiscite can be ignored by Congress - which in the end decides whether Puerto Rico should be allowed into the Union - a victory for pro-statehood Puerto Ricans would add weight to their long call for Washington's full embrace.

"There's little question that Puerto Rico is moving in the direction of statehood," says Robert Pastor, a political scientist from Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass., who specializes in Caribbean studies. "But it's very simple. As a nation, the United States' people have not thought about this issue. Congress hasn't even thought about this issue - other than less than a dozen congressmen and senators."

Indeed, many Americans, asked what they think of Puerto Rico becoming the 51st state, respond with a nonplussed shrug followed by an admission of ignorance about the issue.

There are few shrugs of ignorance or apathy here, though. The island's political parties have spent more than $2 million in bombarding Puerto Rican voters with their messages. And some 73 percent of the island's 2.2 million registered voters are expected to vote Sunday.

When residents go to the polls, they have five options:

* Continue as a commonwealth.

* Become a US state.

* Independence.

* "Free association," essentially independence with treaty ties to the United States similar to former US territories such as the Marshall Islands and Palau.

* None of the above.

A poll published on Dec. 9 by The San Juan Star, a leading local daily newspaper, indicated 49 percent of the electorate will vote for statehood and 45 percent will choose the "none of the above" option. In protest of what they consider unfair wording of the ballot, the traditional advocates of commonwealth are boycotting the plebiscite and telling their supporters to vote "none of the above."

Independence has never been a real issue for most Puerto Ricans, who have little interest in giving up their much-coveted US citizenship. Residents have carried US passports since 1917, but they can't vote for president or Congress - unless they are one of nearly 3 million Puerto Ricans living on the US mainland.

Under commonwealth status Puerto Rico has blended the trappings of sovereignty with the airs of statehood. While the United States provides up to $10 billion a year in federal aid to Puerto Rico and tens of thousands of Puerto Ricans have fought in wars for the US, islanders don't pay federal taxes and keep symbols of autonomy such as an Olympic team.

Anti-statehood advocates have drawn on symbols like these in an effort to sway the vote. The pro-commonwealth faction aired an ad implying statehood would mean the end of Puerto Rico's separate Olympic team. During the spot, an anonymous hand rips the Puerto Rico logo off a basketball player's jersey.

Yet statehood proponents note that US investments have boosted annual per capita income here to $8,500 - one- third the US average but five times higher than in nearby Dominican Republic, and the highest in Latin America. Still, 59 percent of residents on this island of 3.8 million people live below the US poverty line, according to the 1990 census.

And that's something that makes US policymakers less than exuberant about making Puerto Rico the next state. Another flash point is the issue of language. Some have warned that Puerto Rico - where fewer than one-third of the people speak English well and leaders insist statehood doesn't mean English would replace Spanish as the island's dominant language - could become the Quebec of the United States, referring to the restive French-speaking Canadian province.

"At some point folks in the US might wake up and say, 'Who are these peo-ple?' " says Ramon Daubon, a specialist on Puerto Rico for the Caribbean studies group at Georgetown University in Washington. "Puerto Rico is a poor state, the people are not white and not English-speaking. They also want a greater degree of self-government than most states."

Still, Mr. Daubon and others who have studied the issue believe Puerto Rico will eventually become a state, even if it takes a few decades. Islandwide votes on the issue have shown a slackening in appeal for commonwealth. In a 1952 vote on the island's Constitution, some 80 percent supported commonwealth. In the most recent plebiscite - in 1993 - commonwealth got only 49 percent.

In the end, even if statehood carries the day, the vote must be convincing to make people seriously consider the issue. A mere plurality is unlikely to impress Congress. Many members have said they would like to see at least a solid majority, if not two-thirds, voting in support of statehood before they take action.

"It's obvious, from many factors, that there will be a plurality for statehood," says Juan Garcia Passalacqua, a political analyst in Puerto Rico. "The real question now is what is Congress going to do. Do they want to admit a Hispanic state as the 51st state?"

Copyright, The Christian Science Monitor

Follow:

Puerto Rico's future as state remains fuzzy

David Abel

The Christian Science Monitor

12/14/1998

SAN JUAN, PUERTO RICO -- The wording may have been jumbled, but the message was clear: Puerto Rico remains an island divided.

In a plebiscite marred by controversy over how the options were stated, a slim majority of voters favored the option backed by advocates of the status quo when they went to the polls Sunday.

The result is that Puerto Rico has probably pushed back the time when - if ever - it will become the 51st star on the American flag. Many members of Congress - who have the ultimate say in whether the island becomes a state - have been reluctant to consider admitting Puerto Rico to the Union until a strong majority of residents vote for it.

But this weekend's vote is the second time in five years that Puerto Rico has rejected the move to statehood. And the fact that the pro-commonwealth choice actually gained ground this time - up slightly to 50.2 percent - will lead to a bitter argument here over what the real message from the people is.

"To me, the message is clear: The island is still split down the middle," says Juan Garcia Passalacqua, a political analyst in Puerto Rico. "There hasn't been a major change from 1993. The island has been divided for years, and will likely remain so."

Most saw the vote here as an endorsement of Puerto Ricans' strong sense of identity, and their desire to keep their existing relationship with the United States. Currently, Puerto Ricans are American citizens, though they cannot vote for president or elect a voting member of Congress.

Despite the fact that a majority of voters supported the pro-commonwealth position, Gov. Pedro Rossello - who favors statehood - declared victory. After all, statehood won significantly more than any of the other specified options on the ballot, he argued.

But others said that interpretation of the results is ridiculous.

In protest of the wording of the referendum, the majority voted for "none of the above" - the choice backed by pro-commonwealth parties.

One voter here in San Juan put it this way. "I believe in the system we have now," said Teresita Fernandez, a medical aide, after dropping a "none of the above" slip in one of the thousands of cardboard ballot boxes used across the island. "I lived in Brooklyn for 13 years and I know it isn't going to get any better being a state. Now, we have the best of both worlds."

David Abel | The Christian Science Monitor | 11/13/1998

FAJARDO, Puerto Rico -- Hundreds of small fishing boats trail wakes across the turquoise bay off this tropical port town, but scores of them carry a catch that's more than a little fishy.

In the employ of Colombian cocaine cartels, these boats are one of the latest drug-trafficking challenges to confront US law-enforcement officials - a challenge that has only intensified with the chaos wreaked last month by hurricane Georges.

"There was a snowstorm after the hurricane," says Michael Vigil, head of the US Drug Enforcement Administration in Puerto Rico, referring to the latest flurry of cocaine shipments through the island. "It gave them a window of opportunity, and they're taking advantage of it."

The recent upsurge in Caribbean drug trafficking is a response, in part, to smugglers' search for points of entry other than the US-Mexico border. Moreover, say officials in this American commonwealth, Puerto Rico is not equipped to respond with a crackdown.

"We are now in a vulnerable position because a lot of our assets have been transferred to the Southwest border to fight trafficking there," says Jim Weber, FBI special agent in charge in Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands. "Most of our Coast Guard cutters, naval cruisers, and airplanes went to other regions. We're limited to a few US Customs planes, and the machinery is not designed for this type of surveillance."

Fajardo, cited as the entry point of 75 percent of all drugs in Puerto Rico by a 1997 Justice Department report, draws smugglers because it's home to the daily traffic of hundreds of small, wooden fishing boats, called yolas, and is the closest port to an arc of nearby, border-porous islands.

It's also home to thousands of migrants from the Dominican Republic. US authorities say Dominican gangs ferry most of the cocaine and other illicit drugs across the 77-mile Mona Passage to Puerto Rico. The Colombian cartels use Dominican smugglers because they often charge 30 percent less than their Mexican counterparts do to fulfill the role of smuggler, according to DEA reports.

In and around Puerto Rico, the DEA this year has confiscated more than 8,250 kilos of cocaine, 5,400 kilos of marijuana, and 27 kilos of heroin, the DEA's Mr. Vigil says. Officials in Washington say that represents an increase in seizures over 1997.

And the street price of cocaine in the US has plummeted from $ 28,000 per kilo in March 1997 to about $ 14,500 in October, indicating a sharp increase in supply. Officials set a record in the Caribbean last year, when they found 6,700 pounds of cocaine in a tractor-trailer.

Smugglers often sneak their cargo into Puerto Rico aboard small fishing boats, or they dump the drugs in prearranged spots after speeding across the Caribbean on low-slung "fast" boats, which can reach Puerto Rico in as few as 18 hours from Colombia. Lately, the most effective means of smuggling are small planes, which make airdrops after flying near the ocean to evade radar, says the FBI's Mr. Weber.

He attributes the recent upsurge in Caribbean trafficking to "the balloon effect." If you push on a balloon in one place, the bulge goes elsewhere, he says.

That effect has also produced a steady rise in drug-related crime in Puerto Rico. While the number of annual homicides has fallen off since a peak of 992 in 1994, other crimes exceed the rates in the rest of the United States. Authorities say 70 percent of the homicides are drug-related.

The alluring profits of the drug trade have also enticed the island's law-enforcement officials. In September, eight local police officers were arrested on charges of using their police boat to shuttle cocaine from the small island of Vieques, just off the northeast coast near the Fajardo harbor.

Another measure of the increase in drug activity in Puerto Rico is the number of seized shipments found bound for the United States on cargo ships and the number of "mules" caught clandestinely smuggling drugs inside their bodies. Most of the drugs are destined for New York, New Jersey, and Florida, officials say.

"In the last 10 months,... there has been a substantial increase in the number of internal body carriers at airports and international cargo operations," says Ken Cates, associate special agent in charge of the island's US Customs office.

Puerto Rico, a century-old US territory that voted to become a commonwealth in 1952, has long been an attractive port of entry for drug traffickers. The 35-mile-wide island is the closest US territory to Colombia and has more than 300 miles of coastline, often desolate mangrove swamps suitable for stashing illicit goods. Moreover, there are no US Customs checks on shipments to the mainland.

In Fajardo, which was still reeling in late October with blown-out traffic lights, gnarled trees, and windswept hovels, scores of established smugglers were managing to glide across the bay unnoticed.

"These people know when there's an opportunity," Vigil says. "They don't play games."

Copyright, The Christian Science Monitor

By David Abel | The Boston Globe | 11/17/1998

By David Abel | The Boston Globe | 11/17/1998

CATANO, Puerto Rico - This small seaside city, known locally as much for potholed streets as for a crumbling sewer system, may soon find recognition as host to one of the most grandiose monuments in the Americas.

The edifice, a 353-foot-high bronze statue of Christopher Columbus, is the pet project of Catano's mayor, Edwin Rivera Sierra, who stood on the edge of a dock and wept for joy late last month as workers unloaded the first pieces of the sculpture.

"I feel like a child receiving a gift from Santa Claus," Rivera Sierra told reporters while wiping away tears.

All the 2,000 pieces of this sculpture, nearly twice the size of the Statue of Liberty and three times the size of Rio de Janeiro's Christ the Redeemer, have crossed the Atlantic from the artist's workshop in Russia and are stored near its prospective perch in Catano. Still, Rivera Sierra must overcome several obstacles before assembling the statue.

The first is criticism that the huge Columbus will be, at best, an eyesore. The statue features Columbus rising out of a relatively small sloop, which is propped up by a Greek-columned base. One of Columbus's hands grips an angled helm, while the other waves in front of a sail-draped mast.

Zurab Tsereteli, a sculptor from the former Soviet republic of Georgia, has faced criticism for other monuments of his. Tsereteli's 310-foot-high Peter the Great in Moscow was the subject of a removal referendum.

The Columbus statue was intended as a token of goodwill from the newly democratic Russia to the United States. But before Catano was offered the monument, New York, Miami, Fort Lauderdale, Fla.; Columbus, Ohio; and, most recently, Baltimore, rejected it.

"I was there and I told them you have a pretty bay in Baltimore," said Ivan Kazansky, director of Moscow's Union of Sculptors, who advised Baltimore officials against accepting the statue. "I really don't want Mr. Tsereteli to ruin it."

Rivera Sierra says the US commonwealth of Puerto Rico was the natural site for the statue because it is the only place now under the American flag where Columbus had actually set foot.

Then, of course, there is the issue of spending about $30 million on about 600 tons of bronze, so soon after Hurricane Georges destroyed thousands of homes and wreaked billions of dollars in damage on the island.

"In Puerto Rico, our city ranks No. 1 in drug use, No. 1 in violent deaths, No. 1 in high school dropouts, and our city's sewer system is obsolete," said Rosa Hilda Ramos, who heads a local group called Communities United Against Pollution. "In principle, we don't oppose the statue; it's just that our mayor invests so much money, time and effort into things that won't immediately solve our city's problems."

Another woman, Carmen Calderon, 63, waiting for a bus under a dilapidated shelter off Catano's main square, was among those who questioned the mayor's judgment. "The symbol isn't bad; Columbus discovered America," she said. "But how could he think of investing this kind of money when there's sewer water in the streets?"

For his part, Rivera Sierra defended the 31-story statue. He argued that it is an investment in the city's future. Private donors will mostly pay for the project, and the city should begin seeing annual profits of up to $5 million in five years, he says. The mayor also says the statue will create 500 jobs.

With an assortment of fast-food restaurants, souvenir shops, a museum in the base and a lookout tower at the top, Rivera Sierra hopes "The Birth of a New World," the statue's sobriquet, will become as much a symbol of Puerto Rico as the Eiffel Tower is of France.

"Catano will become one of the most important cities of the world, with a huge tourist attraction that will boost the economy of our city for the benefit of all of Puerto Rico," he said of his city, which has a population of about 32,000, an annual budget less than the statue's cost, and such narrow roads that they barely accommodate traffic.

The mayor does not stand alone in support of the statue.

"This is a fabulous idea," said Luis Vega, 50, while tending a used clothing shop across the street from the mayor's office. "It will give us an international spotlight and will bring tourism."

A final hurdle is obtaining the permits. That is no simple matter as questions have been raised on issues including how the statue will affect the local ecosystem and whether it will clog the flow of air traffic into the island's capital, San Juan, which is just across the bay from Catano.

Yet the 49-year-old mayor expects all the permits to be approved by December. He said construction is planned to start in January and finish within 20 months, so the statue will be ready to open on Oct. 12, 2000, Columbus Day.

Gazing through the windows of his cluttered office overlooking San Juan's harbor, Rivera Sierra points to the Isle of Hope, where he expects millions of people will soon see the statue of Columbus as they fly into the capital or sail in on one of the cruise ships plying these turquoise waters.

"Many thought this was a joke, but it's becoming a reality," he said. "It's something our children will always have."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com.

Copyright, The Boston Globe

David Abel | The Sun-Sentinel | 9/1/1999

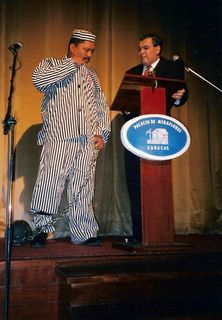

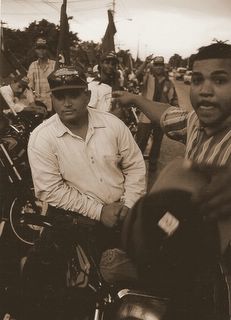

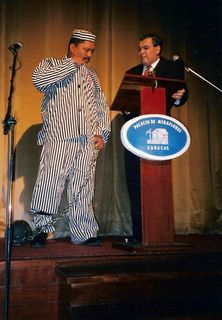

CARACAS, Venezuela --When members of Congress last week resisted an order by a constitutional assembly to strip the legislature of its powers, the president sent hundreds of soldiers in red berets to block legislators from entering the parliament building.

Two days earlier, using tanks and helicopters, dozens of crack special-operations troops launched a blitzkrieg assault before dawn to take back a Caracas prison from rioting inmates.

Now, units from the National Guard have begun patrolling the capital's streets to clamp down on crime.

The increasing presence of the armed forces is part of a plan by President Hugo Chavez to integrate the military into civilian society and take advantage of what he calls "a political resource of the state."

But Chavez's critics argue that by mixing the nation's military with its politics, the president is jeopardizing one of Latin America's oldest democracies and is pushing the country toward a military dictatorship.

The military wields an annual budget in excess of $ 1 billion and has amassed resources over the years for two principal missions: to ensure the security of the nation's oil fields and guard against a spill-over of Colombia's long guerrilla war. But Chavez and his supporters say the military can do more.

The president has ordered about 70,000 soldiers to do everything from repair roads to raise chickens for subsidized sales to the poor.

Chavez himself has deep roots in the military. As an army lieutenant colonel and paratrooper, Chavez led an unsuccessful coup in 1992, for which he served two years in prison.

Despite his background, voters overwhelmingly elected him in December, then returned to the polls in July to elect a Chavez-inspired assembly whose ostensible task is to rewrite the constitution.

Packed with the president's supporters, including his wife, brother and five former ministers, Chavez has 121 of the assembly's 131 votes. As many have feared, the assembly has gone beyond its mandate. Two weeks ago, it assumed many of the powers of the Supreme Court.Last week, assembly members stripped the opposition-controlled Congress of almost all its powers, and this week snatched the one power that remained -- control of the budget.

Assembly members have said they would like to turn their attention to the authority of state governors and city mayors.

Jorge OlavarrBia is one of the 10 members of the opposition that won a seat in the constitutional assembly. "This new constitution is a constitution made for the military," he said. "It has one goal: The concentration of power in the hands of one person," OlavarrBia said.Among its provisions, Chavez's draft constitution would return the right to vote to members of the military.

That right was stripped in the 1961 constitution, the one Chavez claims is the foundation for government corruption, to prevent the return of Venezuela's military dictatorships.

Even before the constitutional changes, Chavez blurred the line between the government and the military.

In July, the 45-year-old president promoted 34 military officers who took part in his bloody 1992 uprising, defying a warning by the Senate that the promotions were unconstitutional. The Senate took its case to the Supreme Court, which has yet to rule.Chavez, the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, also named about 50 military officers to government jobs, despite a law banning military personnel from holding public office.

Among them was Gen. Lucas Rincon, whom Chavez named chief of staff. Within months, Rincon left that job after Chavez fired the commander of the army and named Rincon as the replacement. Some say the reshuffling increased the president's control over the military.

Not all the military supported Chavez's candidacy--but there was a price to pay. The five generals who criticized Chavez during the presidential campaign were forced into retirement this year.The president is also contemplating action against the police in Caracas, a stronghold of the opposition.

"We can intervene in any police force in any municipality, because we are not going to permit any tumult or uproar," he said Sunday during his weekly radio program. "Order has arrived in Venezuela," he said.

Caracas Mayor Antonio Ledezma, a leader of the opposition Democatic Action Party, finds Chavez's threat outrageous.

"The armed forces have specific tasks and none of them have anything to do with maintaining public order," Ledezma said. "To use solders for what the president wants is wrong. The soldier is trained to kill. Not to maintain public order. Any other use is illegal.

"Chavez's supporters, however, say the president is not violating the law as much as he's trying to change the country. Because Chavez thinks the military is beyond reproach, he views its increased role in government and society as a means to cleanse the country of years of corruption. Despite the country's vast oil reserves, which are greater than any nation outside the Middle East, about 80 percent of the people live in poverty."

The president has many new ideas, and we are lucky to have such brilliant people in the military," said Alexis Aponte, the vice minister of the Interior Relations Ministry. "We should use them. We should use the National Guard as a way to assist the police in reinforcing citizens' security. The collaboration will dissuade criminal behavior."

The 120,000-member armed forces, Chavez supporters say, have long been used to carry out civilian tasks. Soldiers have done everything from regulate customs and immigration to provide security and deliver ballot boxes to the National Election Council during elections.

"Undoubtedly there exists a process that a lot of people fear," says retired Gen. Italo del Valle Alliegro, a former minister of defense under President Jaime Lusinchi in the late 1980s. "But I think there is an exaggeration of the problems. Chavez isn't the cause of the problem; he is the consequence. And people overwhelmingly voted for him, knowing what he would do."

Miguel Rodriguez came out of retirement to hawk one of Chavez's favorite books, The Oracle of the Guerrilla, outside the gates of parliament. To Rodriguez, Chavez is Venezuela's long-awaited savior.

Wearing the president's signature red beret as he blasted jibes at Congress through a bullhorn, the 58-year-old said he doesn't worry about the president flouting the authority of Congress or the Supreme Court. He echoes Chavez, saying those institutions "have for too long been corrupt and are now moribund."

Like Chavez, Venezuela's first president to have served in the military in 40 years, Rodriguez says it's time for decisive action.

"The military is there to guarantee the rights of the people," he says. "Yes, we have a history of leaders using the military for their own purposes. But Chavez won't do that. He's taking power for the people."

Copyright, The Sun-Sentinel

By David Abel | The Boston Globe | 9/13/1999

CARACAS -- For years, the long, mountainous border separating Colombia and Venezuela has offered drug traffickers ample opportunity to ferry their cargo.

And smugglers have taken advantage of the easy route to Venezuela's porous ports. Last year, more than 110 tons of Colombian heroin and cocaine passed through Venezuela before it was shipped to the United States and Europe, representing nearly one-sixth of all illegal drugs produced in Latin America, US officials said.

But now traffickers have a faster and more secure route, which before carried the risk of interception by US military jets: air.

At the end of May, President Hugo Chavez announced that US military jets could no longer enter his country's airspace. To do so, he said, would violate Venezuela's sovereignty.

The rejection drew pleas from the United States, which has been increasingly challenged in fighting the flow of drugs from South America since May, when Howard Air Force Base, Panama, shut down to comply with the Panama Canal Treaties.

Chavez, a leader of a failed coup who was denied a US visa before he was elected by a sweeping majority in December, has hampered US interdiction efforts at a critical time. The denial of Venezuelan airspace considerably reduces the effectiveness of the new US antidrug bases in the Dutch islands of Aruba and Curacao, which lie about 50 miles off Venezuela's coast.

"Our challenge is to absolutely defer to Venezuelan sovereignty while doing everything we can to support their ability to cover their airspace," said retired Army General Barry McCaffrey, the US drug policy adviser. "We don't expect a change in Venezuela's position. But we give them the facts. And we hope they reconsider."

These are McCaffrey's points, as described to Chavez in a 90-minute meeting in July: From January to July 20, 29 suspect flights flying from Colombia to Venezuela were tracked by US radar and jets. Since May 28, Chavez's government denied all nine requests by the United States to chase likely drug flights in hot pursuit. And it now takes US planes an additional hour and a half to circumvent Venezuelan airspace, precious time during interdiction missions.

"As traffickers become aware that Venezuelan air space is not being monitored, they're going to be attracted to the weak link," said Brad Hittle, an aide to McCaffrey at the White House's Office of National Drug Control Policy. "You are just opening the window wider to the bad guys."

Chavez's government disagrees. Venezuelan officials say they are more than capable of guarding the nation's airspace. And they say they have a strong record of fighting drugs, seizing more than 2,600 kilograms of cocaine and heroin in the first six months of this year, twice the quantity confiscated in 1998.

"With adequate coordination, Venezuela can handle this," said Alfredo Toro Hardy, Venezuela's ambassador to the United States. Hardy taught Chavez political science at the University of Simon Bolivar in Caracas. "We have plenty of F-16s capable of taking a handoff from US planes. It's just like what happens between police forces when a criminal crosses a state in the United States."

But US officials cast doubt on Venezuela's ability to monitor effectively and pursue traffickers sneaking through its airspace. Since Chavez's reversal of Venezuela's policy in May, his air force has only intercepted one of at least 11 suspect planes, Hittle said.

And many US officials are increasingly wary of Chavez, who, his critics said, is moving to impose a military dictatorship in one of Latin America's oldest democracies.

"It's very unfortunate that the Venezuelan government has taken these recent decisions," said Otto Reich, a former US ambassador to Venezuela in the late 1980s. "The denial of overflights is a significant negative development. Both nations stand to lose."

The anger has reached Congress, where officials have warned that if Chavez's position does not change, the United States may respond by refusing to certify that Venezuela is collaborating fully in the drug war. That would deprive the country of vital trade and aid. The $12 million in antidrug money the United States now gives Venezuela, however, would not be affected.

"Of course, Venezuela's decision should be factored into the president's certification decision process," said Lester Munson, spokesman for the House International Relations Committee. "The United States right now is at its lowest ebb at covering the drug-transiting region. The lack of overflights is part of the problem."

During his recent visit to Venezuela, McCaffrey, the drug policy leader, said he had tried to impress upon Chavez that more than US planes flying over Venezuelan airspace, drug traffickers were violating his country's sovereignty.

This nation of more than 23 million people, moreover, has increasingly become the victim of drug trafficking and use. A surging crime rate between 1986 and this past June claimed 45,009 recorded homicides, which peaked at 4,961 in 1996 and may top that number this year.

Most of the crime results from an economy that has left more than 80 percent of the people living in poverty, police said. In the same time, police said, there were 415,000 violent drug-related crimes.

While McCaffrey and his staff hope Chavez will change his mind, they are not optimistic. And they predict data will soon show drug traffickers are exploiting their new freedom to fly through Venezuelan airspace unimpeded by US jets.

"The jury is still out on how much of a difference this will make," Hittle said. "But the general number of transits are going in the wrong direction. And the simple fact is it will now be easier for traffickers to carry drugs by air."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com.

Copyright, The Boston Globe

By David Abel | The Sun-Sentinel | 8/28/1999

By David Abel | The Sun-Sentinel | 8/28/1999

CARACAS, Venezuela --The sting of tear gas and the force of water cannons sent thousands of protestors gasping for air near the Capitol on Friday, much as they thought democracy was gasping its last in Venezuela.

The unemployed and the well-employed took to the streets to protest a decree issued on Wednesday that stripped Congress of nearly all the power that could help it serve as a balance to the office of the president.

But when defiant legislators called an emergency meeting in a last-ditch effort to salvage their powers, they were stopped by the National Guard, a legion of red-bereted soldiers dressed for battle called out by their charismatic, controversial commander-in-chief, President Hugo Chavez.

"This finally shows the truth: Chavez wants to take all the power for himself and rid the nation of its checks and balances," said Godofredo Marin, a congressman from the Evangelical Party, which opposed Chavez and his reforms. "This was the first violent action of the dictatorship. This is the way it starts. The same thing happened in Cuba."

Friday's unrest capped a week in which the constitutional assembly, a body proposed by Chavez and ostensibly elected to revise the Constitution, limited the powers of the Supreme Court and banned the opposition-controlled Congress from passing laws and curtailed its powers to oversee the budget.Chavez supporters, including his wife, brother and five former ministers, control 121 of 131 seats in the constitutional assembly.

"The Congress has to survive; what the assembly is doing has no legitimacy," said Felix FariDnas, a congressman from the Copei Party, one of several opposition parties, in an interview before surmounting the spiked gate. "The people have elected us. And we will not stay here and watch the destruction of democracy and the institution of the Congress."

But the people elected Chavez, as well, and by an overwhelming majority. Thousands of the president's supporters also took to the streets on Friday, gathering on the opposite side of the Capitol from his critics.

Many in the crowd donned the signature red beret often worn by Chavez, a former army lieutenant colonel and paratrooper who attempted a coup in the early 1990s. They, however, were spared the tear gas and water cannons.

Chavez's supporters said they didn't fear the president's concentration of power. And they believed a strong leader was necessary to do away with years of corruption in a country where 80 percent of the people live in poverty, despite Venezuela's having more oil than any nation outside the Middle East.

"We are here to make sure they don't violate our authority," said William Lara, a Chavez supporter and member of the constitutional assembly, before soldiers allowed him to pass through the Capitol's gates. "We are the ones doing away with the dictators who have ruled for 40 years and stolen everything from the people."

Friday afternoon, Chavez took to the nation's airwaves, assuring viewers in an hourlong speech that the country was at peace and promising the constitutional assembly would continue reforming the country's laws.

He was flanked by the new president of the Supreme Court, the president and vice president of Congress, and the nation's Interior Minister.

"We have to say from Caracas to the world at large that Venezuela is not moving to authoritarianism," Chavez said."The assembly was elected to reconstruct the state. It was authorized by the majority of the state. This is as clear as water."

"We have to say from Caracas to the world at large that Venezuela is not moving to authoritarianism," Chavez said."The assembly was elected to reconstruct the state. It was authorized by the majority of the state. This is as clear as water."

Still, many protesters and congressmen said they feared that the decision of the soldiers to obey the constitutional assembly instead of the Congress represented the first forceful action in the emergence of a dictator.

Although senior congressmen and leaders of the constitutional assembly said they agreed to reach a peaceful solution to the standoff after a session mediated by Venezuela's Catholic Church, legislators said they would not stand by and watch their powers disappear.

Marin and Henrique Capriles, the president of the lower house of Congress, said they intend to protest the constitutional assembly's decree to the Organization of American States and to the United Nations.

They argued the assembly violated a Supreme Court ruling in April that declared its sole mission is to write a new constitution.

"This is a direct violation of the laws that currently govern the nation," Capriles said. "The assembly has no right to make its own decisions. They need to be respectful of our institution. That's the basis for democracy."

Copyright, The Sun-Sentinel

By David Abel | The Boston Globe | 9/2/1999

By David Abel | The Boston Globe | 9/2/1999

CARACAS -- Ramon Meza's killers would later say the 30-year-old ex-convict had it coming.

After Meza burst into a shack west of the capital in August, brandished a pistol, and shot a man who was mourning for three friends murdered days before, irate neighbors chased Meza to his house and torched it, killing him, police said.

Meza is one of a growing number of victims of vigilante justice and other serious crimes in Venezuela.

Crime has jumped by more than 30 percent nationwide since a new US-style judicial system was enacted in July, ending a corrupt system known for judges on the take, police arrests on flimsy evidence, and closed trials.

More than 3,000 inmates have been freed since the new system took effect. And another 10,000 could soon follow, many of them accused of murder, rape, armed robbery, and other serious crimes.

"We have had many years of corruption, and this takes a while to change," said Alexis Aponte, vice minister of the Interior Relations Ministry.

Although many blame the new judicial system for the skyrocketing crime, which in the first weekend of August left 118 corpses in this South American nation of 23 million people, the rash stems from problems ranging from rising unemployment to increasing drug trafficking and use.

And the economic malaise has gotten worse since President Hugo Chavez, a failed coup leader who won a sweeping election victory, took power in February. About the same time Chavez was elected, a 12-year low in the price of oil, Venezuela's main export, squeezed the country's poor, estimated at more than 80 percent of the population.

Despite a rebound in oil prices, however, the economy has sunk further into the doldrums. And crime has festered. Analysts blame an underpaid and under-equipped police force, poor education and swelling slums, and the slowness of officials to adapt to the changing judicial system.

"The data on crime have been horrendous," said Richard Hillman, a specialist on Venezuela at St. John Fisher College in Rochester, N.Y, who was robbed twice and once held hostage in Caracas. "Venezuela has been listed as one of the worst offenders of human rights - way before Chavez. The Chavez policies are attempts to deal with an out-of-control situation."

Yet Chavez's critics say he has avoided the problem by casting blame on the nation's 38-year-old constitution and distorting the influence of the new judicial system, approved by the previous administration. "The problem only gets worse when the president says it's OK to rob if you are hungry or have a sick child," said Caracas Mayor Antonio Ledezma, an opposition leader.

Ledezma acknowledged that police resistance to the new judicial system has played its share in the rising homicide toll. In Caracas, reports of lynchings or revenge attacks against suspected criminals who were released soon after being detained have become a weekly occurrence, he said.

Outside the capital, some officials have gone so far as to tell the police not to intervene to protect suspects or criminals released from jail. Orlando Fernandez, governor of the central state of Lara, told his police they shouldn't waste their time shielding "any crook, rapist, assailant, or murderer."

"It's ridiculous to use the police to protect delinquents," he said in August. "I have to look after honest and decent people. . . . I'm too busy to be protecting criminals."

The new judicial system replaces one largely based on Spanish and Napoleonic codes, where the burden of proving innocence falls on the accused.

The past system often provided little if no representation for the nation's vast number of indigents and had filled prisons with thousands of accused but untried suspects. Of some 27,000 prisoners locked away in Venezuela's notoriously inhumane prisons, about 9,700 have been convicted.

The new code was created to sweep away questionable jailings and curtail corruption allegations against nearly half of the nation's 4,700 judges. Now, police must read suspects their rights, allow them to call a lawyer or relative, and provide evidence to prosecutors soon after the arrest.

While for the most part supporting the changes, Chavez has directed a constitutional assembly to amend certain provisions, such as allowing police more latitude in making arrests and digging up evidence.

The president, a former army lieutenant colonel and paratrooper who spent two years in jail after his bloody 1992 uprising, recently sent special units of the National Guard to patrol the violent streets of Caracas.

He has heightened fears that he would not only bolster police with the armed forces but would replace police with soldiers. "We can intervene in any police force in any municipality, because we are not going to permit any tumult or uproar," he told a weekly radio program. "Order has arrived in Venezuela."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com.

Copyright, The Boston Globe

By David Abel | The San Francisco Chronicle | 12/7/1999

By David Abel | The San Francisco Chronicle | 12/7/1999

LA VEGA, Dominican Republic - An orphan without any education and with little to eat, 12-year-old Lucksene Mezililen followed some friends across the Haitian border some months ago and now scrapes by in this central Dominican city illegally selling candy.

Josephine Losette, 26, recently gave birth to a dimple-faced boy at a maternity hospital in Santo Domingo. Without papers, she worries whether her son will be allowed to go to school in her adopted country. Taking a break from moving earth and pulverizing cement, Aldonis Celesten, 40, supports eight children home in Haiti on the $8 he earns each day under the table helping to build a highway overpass in Santo Domingo.

At least half a million Haitians live illegally in the Dominican Republic. And like Mezililen, Losette, and Celesten, few of them speak Spanish, most live in dire poverty, few have Dominican friends, and many are harassed and arbitrarily deported by Dominican police, who regard them as an unwanted underclass.

"They treat us like we are strangers, like we are animals, that we shouldn't be trusted," Mezililen said after putting down a bin of the sugary Mani candy he had balanced on his head. "It's not easy to live here. But there is nothing in Haiti."

The poor treatment of Haitians living across  the frontier in the eastern two-thirds of Hispaniola - the lush Caribbean island that some 8 million Creole-speaking Haitians share with about 8 million Spanish-speaking Dominicans - has long been a subject of controversy.

the frontier in the eastern two-thirds of Hispaniola - the lush Caribbean island that some 8 million Creole-speaking Haitians share with about 8 million Spanish-speaking Dominicans - has long been a subject of controversy.

But the issue began dominating the airwaves and newspapers in both countries after a report in October by the Organization of American States accused the Dominican government of carrying out mass deportations, and recommended that it grant Haitians legal rights.

The report rebuked Dominican officials for not adopting measures such as issuing undocumented Haitian workers residency cards or legalizing the status of their children born in the Dominican Republic. Despite a provision in the Dominican constitution granting citizenship to anyone born on Dominican territory, as many as 280,000 undocumented Haitian children live without even identity cards, according to Haiti's embassy in Santo Domingo.

"This is a huge injustice. Some of these children only speak Spanish, but they have no documents and they can't even go to school," said Joseph Daseme, who oversees immigration matters at the Haitian Embassy. "This is a problem of discrimination; if we were white this wouldn't be happening."

Officials from the three major parties, however, unite in their dismissal of the OAS report.

Different governments here have long relied on another provision in the Dominican constitution that denies citizenship to those children born of parents "in transit" through the Dominican Republic. The undoc umented Haitians - even those who have lived here for decades - have long been considered in transit.

As for the deportations, which often occur so quickly the Haitians have little or no warning to collect their possessions, immigration officials say they're part of the routine repatriation of 30,000 undocumented Haitians each year.

"They are here illegally and it is our right to deport them," said Ivan Pena, director of Haitian migration at the Dominican Immigration Department. "We are not violating their human rights. The constitution says they are in transit. They aren't Dominicans."

Prejudice, mistrust, and tension between Haitians and Dominicans go back to 1822, not long after Haiti became the world's first black republic. In a bid to topple slavery in the Spanish colony to the east, Haiti invaded the Dominican Republic, ruling harshly until Dominicans gained independence in 1844.

Ever since, many Dominican officials have fanned the flames of racism by warning that Haiti has designs to take over the whole island. The worst conflict between the two countries, however, came in 1937 when the Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo ordered about 30,000 migrant Haitians slaughtered along the Massacre River near the border.

Dominican officials have often attributed problems such as high unemployment and depressed wages to the glut of undocumented Haitians, many of whom have been welcomed across the border to work in low-paying jobs harvesting sugar cane or building roads.

Dominican officials have often attributed problems such as high unemployment and depressed wages to the glut of undocumented Haitians, many of whom have been welcomed across the border to work in low-paying jobs harvesting sugar cane or building roads.

Those complaints have increased in recent years, as the Dominican Republic boasts one of the highest growth rates in the Western Hemisphere, about 7 percent, while Haiti remains the region's poorest country.

Despite the tensions, the past few years have seen unprecedented improvements in relations. For the first time in six decades, the Dominican and Haitian presidents last year reciprocated visits. That followed steps the two governments took in 1996 to strengthen diplomatic, legal, and commercial ties, paving the way last year for the countries to begin direct mail service and to stop routing their letters through Miami.

By David Abel in the Dominican Republic

and Juan Forero in New Jersey

The Star-Ledger

MICHES, Dominican Republic - For 10 years, a fisherman named Lolo has loaded small boats with hundreds of illegal immigrants and crossed the treacherous 70 miles separating this seaside village from Puerto Rico, the last major hurdle for immigrants desperate to begin a new life in the United States.

Charging $350 a head, Lolo and his accomplices make two or three jarring trips a year across the Mona Passage, ferrying some 30 or more people each time - Dominicans, Haitians, Cubans and illegal Asian immigrants, often Chinese and Indians.

"When you're a fisherman and you have the amount of kids that Lolo has, this is what you do," said Cezar, Lolo's 32-year-old cousin and on-board assistant. "Just a few trips a year is more than he would make selling fish all year."

Boat pilots like Lolo, whose family asked that his last name not be used, are just one cog in worldwide smuggling networks that move an estimated 4 million people worldwide across national borders and net $7 billion annually.

But on a recent afternoon, Lolo was on the run, trying to evade government soldiers who had searched for him at his small, burgundy-colored house. "I don't know when I'll see him again," said his wife, who would not give her name. "He could go to jail for a long time."

Increasingly, smugglers like Lolo - small-time entrepreneurs who operate with little overhead or connections - are being phased out by larger, better organized and sometimes more ruthless human smuggling rings that are better equipped to dodge enforcement efforts. Officials believe such organized rings were responsible for taking 23 Chinese immigrants on a tortuous, months-long journey earlier this year from Fukian province to Surinam in South America and on to New Jersey, where they were captured in May.

"What is increasingly clear is the little mom-and-pop operations are now working as subcontractors for the big ones," said Robert Paiva, observer to the United Nations for the International Organization for Migration, which tracks international people smuggling and works immigration officials in various countries. "The little ones are being bought out and serving as branches for the big firms."

The new trend has come since 1993, when a ship named the Golden Venture ran aground off New York with 300 illegal Chinese immigrants, setting off alarm bells among U.S. officials.

The government responded by increasing Coast Guard patrols and embarking on world-wide efforts to train thousands of airport inspections agents and airline personnel to better detect fraudulent travel documents.

Last summer, the Immigration and Naturalization Service also initiated its "Global Reach" program, which included adding 13 field offices to the 24 already operating, putting agents in such key transit countries as Guatemala City, Beijing in China and Copenhagen, Denmark.

U.S. officials and international migration experts said the new efforts have thwarted smuggling vessels bound directly for U.S. waters and the airborne arrival of migrants with false documents.

Yet, there were concerns about the emergence of more organized smuggling, as outlined in a 1995 interagency report submitted to President Clinton warning that "as enforcement efforts become more effective...we can expect the smugglers to become more sophisticated and hard-core criminal groups to become involved in this extremely lucrative trade."

To be sure, smuggling organizations to a great degree remain a loose amalgamation of people - forgers, guides, safe house operators, coyotes, enforcers.

But in the Americas, law enforcement officials and Asian smuggling experts say centrally organized, politically connected criminal networks are handling much of a $3.5 billion-a-year enterprise.

"Unlike occasional traffickers or small rings such as the 'coyotes' operating in the border areas, those crime syndicates are capable of moving large groups of migrants in a single venture," said as assessment paper submitted by the International Organization for Migration at a seminar on human smuggling held this year in Nicaragua. "This is becoming a vicious circle: The more migrants the networks smuggle, the more profit they reap; the stronger they are financially, the more sophisticated they can become in order to move even more persons."

Willard Myers, head of the Philadelphia-based Center for the Study of Asian Organized Crime, said one of the largest organizations - serving Chinese bound mostly for the New York area - is based in Guatemala. "It is a Taiwanese organization, which has gotten larger and larger and larger," said Myers, considered a top expert on Asian smuggling gangs.

Myers said the Guatemala operation "runs all the routes through Central America." He said that though the ring primarily deals with Chinese, the largest non-Latin group smuggled into the United States, "anyone who wants to move through these networks has to have at least some connection" to the Taiwanese.

Another large organization that moves people through Central America was initially based in La Paz, Bolivia, but has in recent years relocated to Sao Paolo, Brazil. It is run by a Peruvian-born businessman of Fujianese descent, Lin Tao Bao, who is considered an architect of organized Chinese smuggling.

These organizations and other groups that focus on transporting Chinese sidestep enforcement measures by transversing any number of countries.

"I don't think there's any country that's immune right now," said Jim Puleo, a senior INS policy advisor assigned to smuggling cases with the State Department's bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs. "There are some who are picked up in Guatemala. Some go through Mexico, some through Colombia, Peru, Venezuela, Guyana...They've tried every one of them."

Guatemala has become an important area of operation, with its large, poorly patrolled Pacific coastline and isolated, unprotected frontier with Mexico. Smuggling experts also say Guatemala, like many developing countries, has had serious corruption problems among its immigration service officials.

Mexican immigration officials, who have stepped up their interdiction efforts on the Guatemalan border, say they have nevertheless continued to see an increase in illegal immigration. Though most migrants are Central Americans, Asians, Africans and Europeans are not uncommon, Mexican authorities said.

"We've seen Hindus (Indians), Chinese, Angolans, also Russians," said Esteban Vega Franco, delegate of the National Institute for Immigration in the Mexican state of Tabasco, which borders Guatemala. "The Chinese, the Hindu, his cost...to the United States can run as high as $25,000."

In a phone interview, Vega Franco said most of the crossings take place along the frontier between Tecun Uman, a dusty border town that straddles the Pacific in Guatemala, and the Mexican State of Chiapas.

The migrants are often loaded in trucks with ventilated secret compartments and given hygienic bags, water and food, Vega Franco said. Then, they're ferried north to U.S. border, with bribes greasing the way if the smugglers encounter trouble.

"It's a business of many millions of dollars," said Vega Franco. "Bring in 50 Chinese and you're talking about a million dollars."

For would-be Chinese migrants, the journey to America most often begins in Fukian province in southern China. From there, migrants are taken by land or sea to Thailand, where they wait for travel documents. The next stop is often Moscow, which they can enter easily and where U.S. officials estimate as many 200,000 illegal immigrants bound for other countries are warehoused.

From there, they might fly into Western Europe and then on to countries such as Ecuador, Venezuela and Surinam, all with active Chinese communities.

The migrants are kept in safe-houses and ferried from one location to another under cover of darkness, mostly by locals. While the guides and safe-house operators usually do not speak an Asian migrant's language, they often learn enough to communicate with their human cargo.

"They don't have to be involved in long conversations. All they have to say is, 'Stop, run, be quiet, don't move,'" said Ko-lin Chin, a Rutgers University expert on smuggling who has interviewed 300 Chinese migrants who've settled in the New York area.

The Dominican Republic has also seen widespread smuggling operations, increasingly migrants from outside Latin America.

"It's more than Chinese crossing from non-Latin American countries. There are Polish people and Turks from Germany," said Fausto Peña, spokesman for the Director General of Immigration in Santo Domingo.

Dominican government records underscore the international nature of the smuggling: Between Jan. 1 and July 23 of this year, 145 foreign national were deported, among them 20 Indians, six Koreans, five Sri Lankans, two Nigerians and four Pakistanis.

Smugglers, though, usually succeed in moving their cargo.

In Miches, the seaside village where the smuggler Lolo lives, would-be migrants are rounded up on cloudy, moon-less nights and taken across steep mountains and dense foliage to secret embarkation points. Before the first wisps of light brighten the sky, they board rickety boats, nicknamed yolas. To get through the 24-hour voyage to Puerto Rico, they bring salami, cheese, crackers, water and rum.

"Sometimes the waves can be higher than a telephone pole and sharks circle the boat," said Cezar, Lolo's cousin.